Nature is not just wild spaces.

"The Kingdom of God is inside/within you (and all about you), not in buildings/mansions of wood and stone. (When I am gone) Split a piece of wood and I am there, lift the/a stone and you will find me." -- The Gospel of Thomas

Had my younger self had a crystal ball, I likely would have been surprised to find that I would one day be associated with any system of spirituality that emphasized nature. Camping, hiking, feeling connected to the wide, wide open; that had always been my sister's MO, but never mine. I didn't dislike the outdoors, but I didn't seek it out, either, and as I grew into my chosen life as an academic I learned to be critical of sentimental or uncritical concepts of nature which posited open space as pure and untouched and contrasted them to contaminated human habitats.

However, it was this analysis, although I didn't know it at the time, that enabled me to eventually rethink how I thought about "nature." For although wild spaces are an undeniably powerful place for human beings to connect with our deepest inner currents, the major reveal for me was how utterly false the concept of nature as existing only in places where, for the most part, humans aren't, really is.

On the face of it the point is obvious to any materialist -- nature is not just everywhere, but it is actually all there is; and as much as environments can differ in hugely significant ways, "nature" itself -- the molecules, dynamics, and forces that make up our world -- knows and recognizes no distinction between the middle of a vast forest and a busy city street. But for me the most important realization came to when I took that knowledge inward; that I am nature, and that the divide between my autonomous self and the natural world is also every bit as false.

I came to this awareness slowly. I had always been interested in neuroscience, genetics, and related fields -- in the science of being human, more or less. And that's not surprising considering how consciousness has pressed down upon me all my life, so much so that the words usually given to people like me -- emotional, intense, crazy, even -- have always seemed so inadequate, limited, and trivializing. In another time and place, this likely would have been funneled into theistic religion -- but alas, I gained an early skepticism of organized religion and by the time I embarked on adulthood I was an atheist. So that left me without a framework or language with which to engage with, nourish, and honor my own interactions with existence.

Early on, I made the classic mistake of American misfits looking for such a structure -- I turned to individualism and all its accompanying lies about who we are and how human creatures find happiness. I engaged in many classic cliches -- a fascination with Freidrich Nietzsche, for example -- and quite a few eccentric ones, such as a nerdy infatuation with the "founding fathers." These mistakes also seriously retarded my political development, keeping me locked in the lies of capitalism and imperialism far longer than I should have been (ie, I knew better). But once I had done enough living to really grapple with what arrogant bullshit individualism is, my politics eventually evolved from there, and by the middle of graduate school I had found my home among the socialists, anarchists, and radicals of the earth.

But while this provided me with the ever-necessary something-larger-than-myself, and a set of values and guidelines for living an ethical life, it didn't give me a framework for interpreting and understanding my subjective experiences of being alive. What to do with all these FEELS?! If anything the prejudices that came with my shift in political perspective made my need to experience and share "the feels" more difficult; weren't all my emo-inclinations the hallmark of the self-absorbed bourgeoise? Of course, my complete lack of supernatural belief didn't help matters either; I remember the awkward response of my co-hosts, on an atheist podcast I did for a while, when I told them that I understood what people meant when they said they are "spiritual but not religious." The problem was, I thought at the time, that we simply don't have words for those experiences outside of a religious framework.

And I still think this is the case to some extent, but I've also realized that another way to approach the issue is to rethink what we mean by spirituality. Because what did I mean?, exactly? I meant that I experience life intensely; I feel great joy, great anger, great fear, and great love nearly every day of my life. When these normal experiences are even more accentuated by special moments or circumstances, they reach the zone of being nearly incommunicable to others, though the gods know I've tried. And beyond that, despite being a materialist, I feel that these experiences have meaning beyond myself; that I'm tapping into something that has its origins beyond my own body and bone.

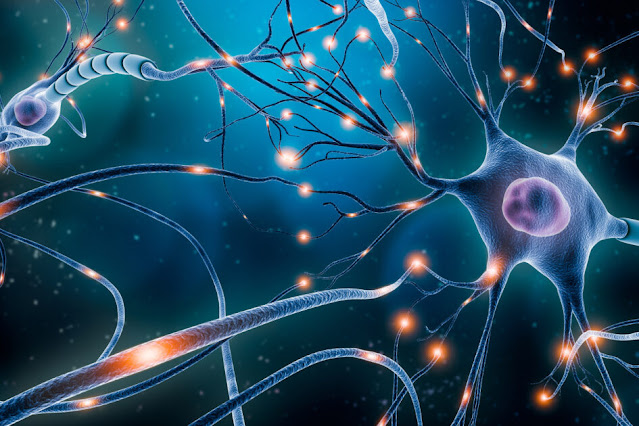

And of course they do; because I am one end product of millions of years of evolution, and billions of years of cosmic history. I started connecting these dots very slowly; a few years ago I finally got a somewhat abstract tattoo of neurons I'd long wanted, as the wonder and reverence I had for the beauty and mystery of the brain had been with me since young adulthood. And around the same time, I started looking more closely at a period in history that had recently drawn me in; the Viking Age. I'd already been listening to a podcast and watching the absolutely amazing The Last Kingdom for a couple of years when I decided to also watch Vikings and begin reading books about Germanic paganism as well. I'll save the details for what drew me into this world for another post, but when I discovered there was a group of atheist pagans who shared my sense of reverence and respect for existence yet did not believe in the supernatural, I had finally found a complete and external framework that would allow me to acknowledge and celebrate my own spirituality in the context of a broader community.

And what I've come to learn how to fully immerse myself in every day is this simple truth: nature is "in here" as much as it is "out there." And by "in here" I don't only mean your own body and brain, but your immediate and everyday surroundings. When I lay down in the afternoon to take a nap, the sun streaming through my window, I am taking refuge in a shelter just as my ancestors did; just as wolves and bears do in their caves and dens. When I melt at the delicious taste of grilled food, I am experiencing the same comfort as did all my ancestors before me, who met around a fire to eat and could be freed, for the moment, from the fear of failing to survive. When I find myself compelled by the beat of a drum to dance, I'm being compelled by something so human and yet also so deeply mysterious that science still today does not completely understand the dynamics between human emotion and music. But we know it goes back as far as our human consciousness does.

These days I spend a lot of time in my backyard, tending to my plants and, much to my amazement -- I've never been one for gardening until now -- finding myself simply staring at them for longer than I had ever thought possible. While I'm there, sometimes birds pop into the backyard to eat the birdseed from the feeders, or squirrels scramble up the fencing. If I'm real lucky, a neighborhood cat might come by. I can hear the sounds of my neighbors going about their day and also enjoying their small outdoor spaces; I think about how this instinct to go outside, to lay in the sun, to cook, to sit in a circle with friends and talk, has never dulled a bit, despite all our supposed distance, in the modern era, from how we used to live. And then the distance between me and them, between my autonomous self and the concrete or soil beneath my feet, suddenly melts away; and I know I wasn't wrong to suspect all along, that there's something sacred in all of it.

A common response to materialism is horror; how can you go through life believing nothing is magical? This response is understandable, seeing how we've been trained -- by the monotheistic tradition, by the Western philosophy of mind versus matter -- to divide the world into sacred and profane, holy and contaminated, nature versus humans. But the other option is, of course, the opposite; these divisions are false, and its all sacred, its all magical; that which we understand the specific dynamics of, and that which we do not and likely never will. And you don't need to travel to the mountains or the ocean to see this, feel this, and know this. While there's no doubt that wild spaces greatly assist with these experiences -- and the science and research on that is also amazing -- it is far from required. For the physical and sacred world -- with all its history and meaning -- is inside you, and all around you.

Comments

Post a Comment